By John Hutchinson, M.D., New York, N. Y.

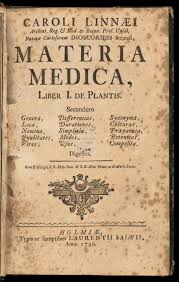

The debatable status of Materia Medica appears ever to be taken for granted. I wonder if this is not because we are apt to cherish an objective perception of therapeutics. That is, there are, let us say, three methods of drug employment: allopathic, Homoeopathic and eclectic. Question: Do you make an allopathic selection, or homoeopathic selection, or eclectic selection? Put in this way, the case seems simple, and it is plain that the three pharmacopoeias have nothing I common but words.

The task of prescribing claims much more than the consideration of favorable remedies. It presupposes definite notions of the right way to approach those remedies. And it by no means views Homoeopathy as a subsidiary element in medicine. The late William James once quoted a wonderful remark made by an unlettered workman. It was this:

“There is very little difference between one man and another, when you go to the bottom of it. But what little there is very important.”

The very important difference between one remedy and another is not sufficiently clear in many cases. And we may forget that the great importance consists in the slight differences which may exist between certain remedies. And even if we remember, this fact cannot be fully comprehended, for we know that Materia Medica is not understood when taken by itself alone. Without the Organon as guide and expounder the treasures are not entirely seen. It is often very hard to find the similar remedy for a trying case, to say nothing of the simillimum.

It Materia Medica were taught in conjunction with the Organon, there would; at least, be no confusion about the former’s employment. There would be no chance to lay down the rule that a certain remedy must always be used in the 3x, that Pulsatilla will not work above the 6th, that Bryonia should be given in the 30th, and that high potencies do not act; that Phosphorus must be freshly prepared in every case, not to say that it should smoke, and that Aconite is never indicated unless you reach your patient before he sends for you.

Chronic features obtain in so many patients for whose acute disorders we are called upon to prescribe, that before we have time to realize it the case assumes larger proportions. The problem becomes a philosophical one despite our praiseworthy aims in the line of simplicity. In the situation, hourly forced upon us, what should we do without the counsel of the Organon?

For instance, what aid can we command that approaches its equivalent? Whether the case has been mismanaged, whether it presents incurable features, whether it demands immediate relief from some distressing feature, whether for any relief whatever it must depend on a long and painstaking search for caved long before, whether its psychological phases deserve the most care, and what must be contemplated in any and every prescription, – these and scores of other queries are there are here many physicians who are so familiar with its pages that as a these single problems are mentioned they are able to refer to the exact paragraph or paragraphs containing the needed information. I wish that w all could do it. However, there is no reason for useless regret. We all know the book, and with it at hand, we are in full armor.

Perhaps some of us can go back in memory to the time of first seeing the pages of symptomatology in Hahnemann’s Chronic Diseases. Tho some of us that first view was astounding. Chronic Diseases! And here are only symptoms, subjective and objective! Where are the diseases? Well, the answer to that was made by the late Dr. William P. Wesselhoeft, who, on taking the long case of a new patient, was asked by the latter, replied, holding the closely-written pages before the patient’s eye – “That is your trouble!”

Hahnemann’s Phrase for the diagnosis – A “species” of typhoid fever, a “species” of pneumonia, impresses me as the acme of exactness in diagnosis. As is well known by us all, Hahnemann was accustomed to make the most thorough physical examinations of his patients. He knew obviously the general diagnostic appellation for the case. But he went much further than this when he set his individual case apart from the general majority of cases by that word “SPECIES.” That seems to emphasize the fine difference that should always obtain between the ordinary diagnosis and the diagnosis made by the homoeopathist.

The species of pneumonia calling for Ipecac is not the same pneumonia as that calling for antimony. And so we might carry the statement almost through the Materia Medica. The point is, to attach the importance, not to the broad, but to the narrow classification. That is what diagnosis is for. It is possible that diagnosis, as ordinarily understood, is responsible for that misapplied slogan, “The Totality of Symptoms,” for so long now degenerated to the numerical totality, and having confused disastrously for any minds the peculiar symptoms of the patient with the inevitable and commonplace symptoms of the disease.

You will be interested, I know, in thee following letter from a member of the homoeopathic school of medicine:-

“What splendid results have been accomplished in preventive medicine by the use of typhoid bacterins in our army, where they have practically wiped out the disease in the last three years. Then there is Acetezone, that splendid intestinal antiseptic, which does so much to prevent intestinal putrefaction and distension of the abdomen with gases. And surely your must realize the great value of calomel or castor oil in the early stages of the disease, as well as of Somnos in typhoid delirium and insomnia.

I” thank the Lord daily that he has permitted me to see the glorious 20th century with its great advance in preventive medicine. What a privilege to use such agents as Salvarsan for the cure of syphilis, Phylacogens for the treatment of rheumatism, and specific sera for combating meningitis, pneumonia and scepticaemia.”

The man who wrote this graduated from a homoeopathic college and passed his examinations well. But even our old school friend knows better than to make such statements. Is it not humiliating that a homoeopathic physician should be governed by such convictions in the face of his heritage? It might be interesting to know what thoughts cross his mind, as he learns, from time to time, that the well-studied and scientifically-applied remedies of our Materia Medica are being rediscovered and crudely applied by the old school. Say, Apium virus, in good Punishing doses for rheumatism. Mistletoe (Viscum, album) for the heart that goes wrong somehow; Crotalus for sciatica that defies surgery, Bufo for epilepsy, wherever and however seen, et cetera ad nauseam.

The published errors in diagnosis remind us that we are bound to excel such statistics. In a leading hospital outside our school, with every facility for diagnosis, in only 22.5, per cent. Of the autopsies was the diagnosis confirmed. In 14 per cent. It was partly correct, and in 34.1 it was entirely wrong or not made at all. What shall we say of the diagnoses in nonfatal cases? It is probably safe to estimate that in 10 per cent. Only could the diagnosis be depended upon if taken. American Medicine says to this: “So let’s get to work in the matter of finding out what kills so many people prematurely.”

That last quoted sentence is astoundingly suggestive. Further, it points a certain moral. Let it be remembered that we are confronted with drug diseases and worse toxemia wherever we are called. We receive every day cases that have been coolly prognosed hopeless after having received the course of treatment that may have made them so. I see no solution for these problems, but in our Materia Medica rationally availed of by the wisdom of the Organon. That the latter should be neglected in conjunction with the teaching of the use to be made of symptomatology is most regrettable. Because it is neglected, we have the state of mind evidence by the physician who thanks God for Salvarsan and its ilk for use on other people.

As to the form and size of our Materia Medica, given us by master minds, we cannot spare a line, nor can we improve on Hahnemann’s arrangement that has been repeatedly endorsed by our best proves and clinicians. The possibilities of our Materia Medica are unlimited. And I would only insist that it is the privilege of every practitioner to add his quota to the already priceless mass of authentic provings.